When it comes to wine, we often focus on grapes, winemaking techniques, and styles. But behind every great wine lies a deeper force—geography. In the WSET Level 3 syllabus, understanding how mountain ranges and rivers affect vineyards is critical. These natural features help shape a region’s climate, soil, and topography, directly influencing ripening patterns, grape health, and ultimately, the style and quality of wines—including iconic sparkling and sweet expressions.

In this guide, we’ll explore the key mountain ranges and rivers across WSET Level 3 countries and how they impact viticulture.

France

Mountains:

Pyrenees (Southwest)

Massif Central (Central France)

Vosges Mountains (Alsace)

Alps (Southeast)

Rivers:

Loire, Garonne, Dordogne, Gironde, Rhône, Seine

Effects:

The Vosges Mountains in Alsace block rain from the west, creating a dry, sunny climate, ideal for aromatic whites like Riesling and Gewürztraminer.

The Massif Central elevates vineyards in the Loire and Languedoc, moderating temperature and improving acidity.

The Rhône River funnels the Mistral wind, cooling southern Rhône vineyards and reducing disease pressure.

The Gironde Estuary in Bordeaux helps regulate temperatures and reflects sunlight, aiding ripening.

Rivers like the Loire and Garonne create humid microclimates that allow for Botrytis cinerea, essential in sweet wines like Sauternes.

Italy

Mountains:

Alps (North)

Apennines (Spine of Italy)

Rivers:

Po, Arno, Tiber

Effects:

The Alps block cold northern winds and create foothill vineyards in Trentino-Alto Adige and Piemonte, ideal for high-acid whites and Nebbiolo.

The Apennines provide elevation in regions like Tuscany and Abruzzo, helping retain acidity in reds like Sangiovese.

The Po River Valley is fertile but cooler, supporting sparkling wines like Lambrusco and Metodo Classico Franciacorta.

Rivers moderate temperatures and contribute to morning fog, aiding Botrytis for sweet wines in Umbria (Orvieto) and parts of Veneto.

Spain

Mountains:

Cantabrian Mountains, Pyrenees, Sierra de Gredos, Sierra Nevada

Rivers:

Ebro, Duero, Tajo, Guadalquivir

Effects:

The Cantabrian Mountains shield Rioja from Atlantic rain, creating a continental climate with cool nights—ideal for Tempranillo.

The Pyrenees offer high-altitude vineyards and freshness in regions like Somontano.

The Ebro River valley allows airflow and irrigation, vital in Rioja and Navarra.

Duero River helps moderate the hot climate of Ribera del Duero, allowing for structured, age-worthy reds.

Fog and elevation in areas near rivers help in sparkling Cava production in Catalonia.

Germany

Mountains:

Taunus Hills, Hunsrück Hills, Haardt Mountains

Rivers:

Rhine, Mosel, Nahe, Main

Effects:

Rivers like the Mosel and Rhine reflect sunlight, helping Riesling ripen in this cool continental climate.

Steep, south-facing slopes near rivers ensure maximum sun exposure.

Humidity from rivers encourages Botrytis in regions like Rheingau, key to producing Beerenauslese and Trockenbeerenauslese sweet wines.

Protected valleys limit frost risk and aid in long growing seasons.

Portugal

Mountains:

Marão Mountains, Serra da Estrela

Rivers:

Douro, Tejo

Effects:

The Marão Mountains divide the Douro Valley from maritime influence, making it one of the hottest wine regions—perfect for Port.

Terraced vineyards on the Douro River create ideal conditions for sun exposure and water access in steep terrain.

Altitude variation allows for both fortified sweet wines and table wines with freshness.

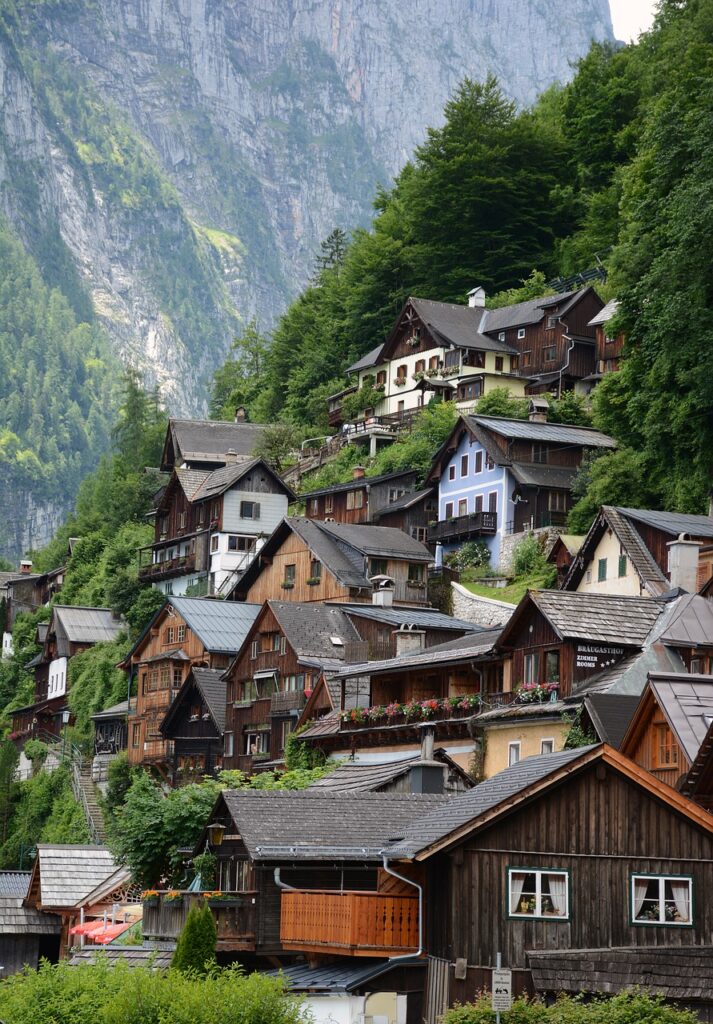

Austria

Mountains:

Alps

Rivers:

Danube, Krems, Traisen

Effects:

The Austrian Alps cause a rain shadow effect in eastern wine regions like Wachau and Burgenland.

Danube River moderates temperatures, creating cool, foggy mornings followed by sunny afternoons—ideal for Grüner Veltliner and Riesling.

Rivers allow for noble rot in Neusiedlersee, producing luscious sweet wines like Ausbruch and Trockenbeerenauslese.

Hungary

Mountains:

North Hungarian Mountains

Rivers:

Bodrog, Tisza

Effects:

The convergence of the Bodrog and Tisza rivers in Tokaj creates autumn mists—ideal for Botrytis in Tokaji Aszú.

Volcanic foothills in the region add mineral depth to wines.

Cool climate moderated by river fog and sunshine balance sugar and acidity in sweet wines.

Greece

Mountains:

Pindus Mountains

Rivers:

Limited major rivers (minor valleys contribute to microclimates)

Effects:

The Pindus range provides altitude to combat southern heat in regions like Naoussa, ideal for Xinomavro.

Altitude and mountain breezes help preserve acidity.

River valleys and proximity to the sea offer some moisture and fog for Moschofilero and Assyrtiko.

South Africa

Mountains:

Cape Fold Mountains

Rivers:

Breede, Berg, Olifants

Effects:

Mountain ranges provide cooling effects, shade, and complex topography in areas like Stellenbosch.

River valleys offer fertile land and are used for irrigation in warm inland regions.

Cool air from the mountains and rivers helps develop acidity in Chenin Blanc, Pinotage, and MCC sparkling wines.

USA

Mountains:

Coastal Ranges, Sierra Nevada, Cascade Range, Appalachians

Rivers:

Columbia, Russian, Sacramento

Effects:

In California, coastal mountains protect Napa from ocean fog but allow cool air to funnel through gaps like the Petaluma Gap, essential for Pinot Noir and Chardonnay.

In Washington, the Cascade Range creates a rain shadow, making the Columbia Valley dry and sunny—great for Merlot and Cabernet Sauvignon.

River valleys enable irrigation and create cool morning fogs, essential in regions like Russian River Valley.

Elevation and continental climate in the Finger Lakes (New York) near deep glacial lakes aid in Riesling and sparkling wines.

Chile

Mountains:

Andes Mountains, Coastal Range

Rivers:

Maipo, Rapel, Maule

Effects:

The Andes provide high elevation vineyards with diurnal range, increasing acidity and aromatics.

Snowmelt from the Andes feeds irrigation.

Cool air descends from the Andes at night, helping grapes like Cabernet Sauvignon ripen slowly.

Proximity to rivers and valleys like the Maipo creates ideal conditions for structured reds and vibrant whites.

Coastal range gaps allow fog and sea breezes, supporting sparkling wine production in Casablanca Valley.

Argentina

Mountains:

Andes Mountains

Rivers:

Mendoza River, Tunuyán

Effects:

High-altitude vineyards in the Uco Valley (up to 1,500m) reduce heat and boost acidity in Malbec.

The Andes provide glacial meltwater for irrigation.

Sunny days + cool nights = perfect ripening conditions.

Some cooler areas like Patagonia are emerging for sparkling wines and Pinot Noir.

Australia

Mountains:

Great Dividing Range

Rivers:

Murray, Murrumbidgee

Effects:

The Great Dividing Range creates altitude-based vineyards in regions like Orange and Canberra, preserving acidity in whites.

Inland river valleys like the Murray-Darling are warmer and produce high-volume wines using irrigation.

Cool pockets near mountain foothills support sparkling wine production in Tasmania and Yarra Valley.

New Zealand

Mountains:

Southern Alps

Rivers:

Waipara, Wairau, Clutha

Effects:

The Southern Alps protect Marlborough from wet westerlies, giving sunny conditions for Sauvignon Blanc.

Rivers cut through valleys providing free-draining soils and fog-prone microclimates.

High UV light + cool nights = expressive aromatics and balanced acids.

Cool climate and altitude in Central Otago support Pinot Noir and traditional method sparkling wines.

Final Thoughts

Mountains and rivers may not be as glamorous as Grand Crus or rare grape varieties, but they are the invisible architectsof great wine. From creating temperature variation to moisture control and sunlight reflection, these geographic elements are crucial to understanding wine styles at the WSET Level 3 level—especially when it comes to sparkling and sweet wines, which often rely on specific microclimates.

By understanding how geography shapes viticulture, you’ll not only pass your exam—you’ll start tasting the landscape in every glass.